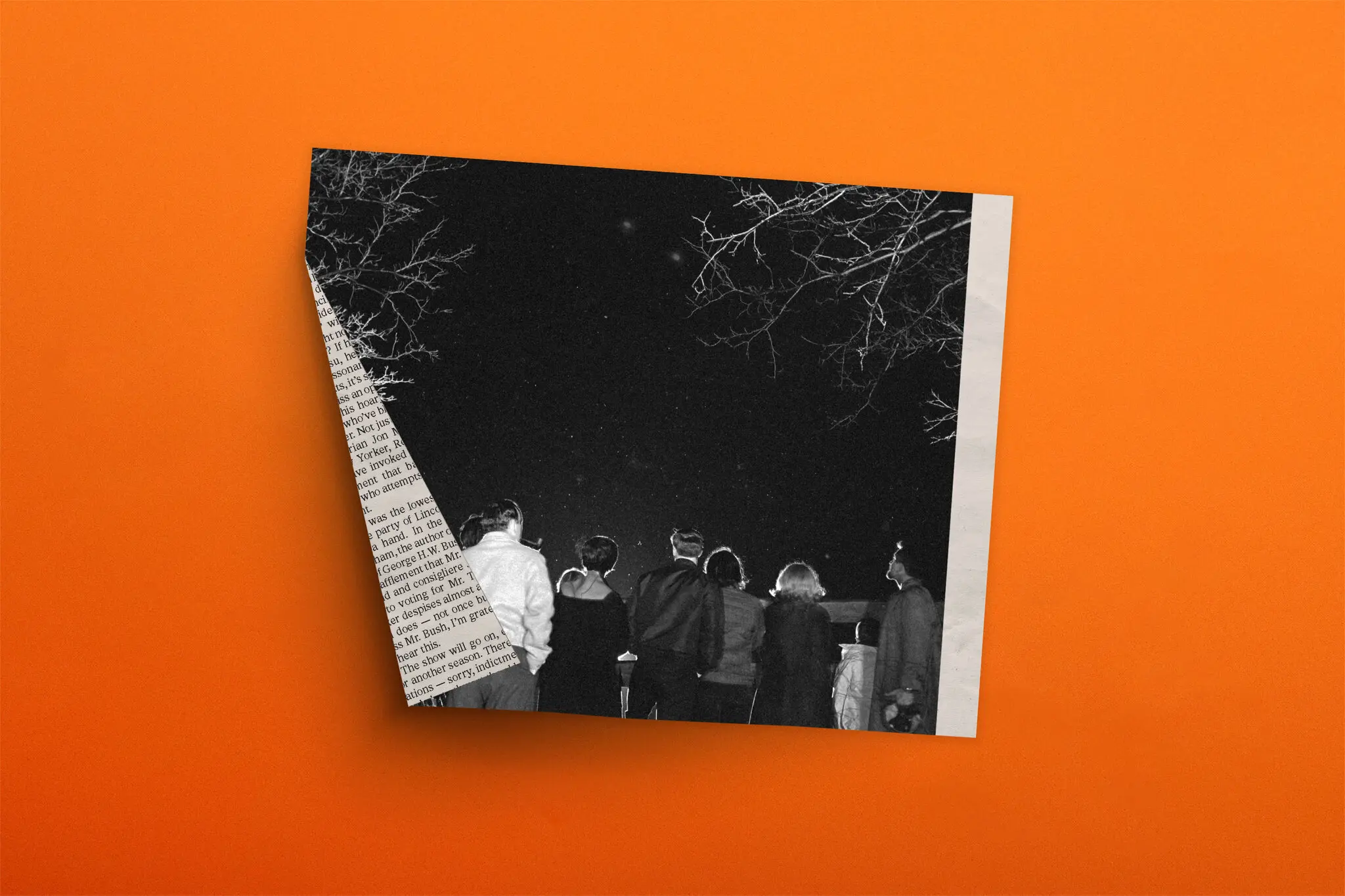

Wait, Are there actually Aliens?

Shared by: PX Editorial Team

Source: Scientific American

Image credit: Illustration by The New York times; photograph by Bettmann/Getty

Browse by Phenomena

View Popular Filters

Shared by: PX Editorial Team

Source: Scientific American

Image credit: Illustration by The New York times; photograph by Bettmann/Getty

Shared by: PX Editorial Team

Source: Scientific American

Image credit: Illustration by The New York times; photograph by Bettmann/Getty

When the Hydro-Québec power grid collapsed on March 13, 1989, the outage plunged the entirety of Quebec—more than six million people—into darkness for several hours. The event was triggered by a ferocious storm, but the tempest wasn’t of Earth’s making. Instead the source was the sun: our nearest star had unleashed a swarm of high-energy particles and radiation that wreaked havoc on our technological infrastructure.

Yet that event wasn’t a fluke, scientists now know. Nor was it particularly powerful. Careful analysis of evidence gathered from tree rings suggests that similar but far larger barrages have repeatedly struck Earth in the relatively recent past. Researchers have long considered our star’s sometimes extreme activity to be the culprit in these larger events, but new work incorporating insights from tree physiology and our planet’s carbon cycle challenges the idea that solar storms are responsible.

This shift in thinking began roughly a decade ago, when Fusa Miyake, a cosmic ray physicist, began analyzing the wood of long-lived cedars felled on Japan’s Yaku Island. Miyake, then a graduate student at Nagoya University in Japan, was meticulously extracting carbon-rich cellulose from the trees’ rings, each of which typically recorded a whole year’s worth of growth in a span of less than a millimeter. Her goal was to measure the amount of carbon 14—a radioactive isotope of carbon commonly used to date archaeological artifacts.

Carbon 14, also known as radiocarbon, is produced naturally on our planet when high-energy radiation and particles emitted by the sun, other stars and various cosmic cataclysms interact with atoms in Earth’s upper atmosphere, most notably nitrogen. Radiocarbon is also a by-product of human activity—the isotope’s atmospheric concentration doubled during the mid-20th century heyday of cold war–era atomic weapons testing, when the U.S. and other nations detonated hundreds of nuclear bombs in the atmosphere.

View Original Article